|

Duomo

Santa Maria Assunta

Piazza Duomo |

The word duomo comes from the Latin domus, meaning the house

of the Lord. So nothing to do with domes.

History

The first church on this site, traditionally said to date from the 7th

century,

was destroyed by fire during the Hungarian invasion of 899 and rebuilt and

consecrated on 29th December 1075 by Bishop Ulderico. This church was badly damaged by

the

earthquake on the 3rd of January 1117 and rebuilt in Romanesque style, in

the

1120s, this church can be seen in Giusto de' Menabuoi's frescoes in the

Baptistery. Another church was built by Bishop Stephen da Carrara in 1400,

the previous one having fallen down. This one must itself also have been poorly

constructed because plans were made for a new church in 1524.

This, the current cathedral, was designed by Andrea della Valle and Agostino

Righetto, reflecting the design of earlier Paduan churches. Work began in

1547, but was only completed in 1754, with the façade remaining

unfinished. Paduans are said to have once boasted that the plans for this

church supplied by Sansovino were rejected in favour of those commissioned

from Michelengelo, but the fact that these plans were also ignored is evident from the

church's eventual form. Damaged during a Royal Air Force bombing raid,

targeting the railway marshalling yards, on 22nd March 1944.

Interior

The key word is huge - the aisles, with their immense chunky

pillars, supporting oversized capitals, which separate them from the nave

which has two cupolas over it, the side chapels, which are so deep they

might be extra transepts, except that the actual transepts are even bigger

with enormous altars at each end. Another appropriate word is 'dull'.

Art Art

No labels on the paintings and no guidebook available. The paintings in

here are all 18th-century or newer.

The second and third (deeper) chapels on the left have altarpieces by

Pietro Damini - Saint Jerome in the Desert with A Donor and a

Crucifixion with Mary Magdalene and Catherine of Alexandria. The

latter is the Chapel of Gregory Barbarigo, a 17th century Bishop of Padua,

who is himself lying behind a glass panel in the altar, which is the work

of Giorgio Massari. The row of dark bronze busts are of the patron saints

of Padua - Daniel, Justina, Anthony and Prosdocimo. The next chapel has an

unobjectionable Virgin and Child with Saints... with a curly-haired

baby John the Baptist, of 1716 by Gian Antonio Pellegrini.

The third chapel on the right has a dark and distant

Virgin and Child with Saints attributed to Padovanino.

Reports of paintings by Stefano dell'Azare, Tiepolo, and Paris Bordone

could not be confirmed. Ditto a

Virgin previously wrongly ascribed to Giotto

- it was as a Giotto

that Petrarch bequeathed it to his friend Francesco da Carrara. Giotto

- it was as a Giotto

that Petrarch bequeathed it to his friend Francesco da Carrara.

A Byzantine-style Virgin and Child also mentioned might be the one

read about in reliable reports of a 17th-century copy of a late

13th-century Virgin and Child, documented as used every year in a

Christmas mystery play here.

I have since

also read about three works by Nicoletto Semitecolo in the sacristy here. Two

panels depict scenes from the Life of Saint Sebastian and one is a

Byzantine-looking gold-background Virgin and Child (see right).

The

transept has, as well as many tombs, a number of 18th-century-looking

canvases too high to see. As does the choir.

There are nasty melting-looking modern sculpture figures on the steps up

to the presbytery, which has carved walnut stalls by Filippo Parodi, a

pupil of Bernini who was also responsible for the very baroque reliquary

chapel in the Santo. Even the crypt is uninteresting.

Lost art

A sculpted bust of Bishop Stefano da Carrara of 1402 by an

anonymous sculptor is in the Eremitani Civic Museum.

The Epistolary of Giovanni da Gaibana, signed by the named

scribe in 1259 and made for the Duomo, is now in the Biblioteca Capitolare

in Padua. Padua was a leading centre for the production of illuminated

manuscripts in the mid-13th century, and the Byzantine-influenced style

known as Gaibanesque was very influential. |

|

|

|

Opening times

Daily 7.30 - 7.30

|

|

The Baptistery

|

|

History

Romanesque and brick and originally built around 1260. The interior was frescoed by the Florentine Giusto de' Menabuoi in the

mid-1370s,

the work commissioned by Fina Buzzacarini, the wife of

Francesco I da Carrara, the Carrara family having been

Giusto's best

patrons. Fina got Giusto to paint her and her three daughters as onlookers

to the birth of John the Baptist, the Crucifixion, the Way to Calvary and one of Christ's

miracles. The crowd in the latter also includes her husband and Petrarch.

Also appearing is Fina's sister Anna, the abbess of

San Benadetto, another church

which benefited from Fina's patronage. Husband and wife were buried here, in 1393 and 1378 respectively,

and the frescoes were finished by 1393.

Interior

The bust-length Christ Pantocrator is in

the centre (see right) surrounded by a heavenly kaleidoscope, in

five circles, of angels, patriarchs and matriarchs from the Old Testament,

and saints. Below Christ is the Virgin in the orant posture.

Beneath her the Creation of the World in the drum and beneath this

is the large Crucifixion, with the apse below it. Also in the drum, with its few randomly-spaced windows, there are

more scenes from

Genesis,

beginning with The

Creation. The pendentives have The Evangelists seated at desks,

each flanked by prophets. On the walls below scenes from the Life of John the Baptist

are on the south wall and

the Life and Passion of Christ make up the rest, ending with the

Pentecost in the dome of the apse.

Scenes from the Apocalypse line the walls of

the apse, over the entrance to which is The Crucifixion. The altarpiece

here, of The Virgin and

Child and Saints with Scenes from the Life of Saint John the Baptist (see

below)

is also the work of Giusto.

On the west wall opposite is the tomb canopy of Fina Buzzacarini

(see photo below right),

clearly modelled on those of the Carrara lords now in the

Ermitani church.

Her tomb chest, which almost certainly featured an effigy, and the epitaph are lost,

removed by the Venetians a few years after they conquered Padua in 1405,

along with Francesco's tomb. (Giusto was also buried in here.) In the fresco under the arch of the canopy Fina kneels to the

favoured right of the Virgin, is the same size as the holy figures, and is

unusually unaccompanied by her husband, which also makes the composition

asymmetrical. She is being presented by John the Baptist

and John the Evangelist who stand behind her. On the other side of the Virgin's

throne are local saints Daniel, with a model of the city, and Prosdocimus,

the first bishop of Padua who was renowned for the number of baptisms he

performed, and so appropriately mirrors John the Baptist's pose and

position on the left. In the space left by the removal of the tomb

chest and epitaph is a later full-length fresco of Saint John the Baptist

surrounded

by supplicants.

The interior was 'cruelly' repainted by Luca Brida in the 18th century but that work was reversed and

recent cleaning has left the frescoes looking fine. Damage to lower parts

of lower scenes, especially on the north wall, but still vivid colours on

upper levels.

The exterior was covered in frescos too,

but these have long since been washed away, although there is a small

fragment showing a woman's profile by Giusto in the Bishop's Palace.

Baptistery opening times

Daily 10.00 - 6.00

Closed Christmas, New Year’s Eve and Easter.

Bibliography

Anne Derbes Ritual, Gender & Narrative in Late Medieval

Italy

Fina Buzzacarini and the Baptistery of Padua' 2020

A big book, with a long title, concentrating on the influence on

the imagery in the baptistery of the religious and civic rituals enacted

there and the woman who commissioned the work. Investigating Fina's

influence informs the whole book, even the in-depth analysis of the

Biblical cycles, as does the perceived feminist agenda in the female-dominance

in the themes and figures.

|

|

|

|

Beato Antonio Pellegrino

Oratory Church of St Anne

Via Beato Pellegrino |

|

Ognissanti

Via Ognissanti |

History

The church and convent were built by Benedictine nuns from Santa Maria

di Porciglia whose previous home had been destroyed by war in 1509 . They

brought with them the remains of beato Antonio Manzoni called

"Pellegrino". The complex was built to the designs of Vincenzo Dotto.

Following the Napoleonic suppressions and the expulsion of the

Benedictines the complex was used as a barracks and in 1838 made into a

hospice, undergoing major restoration in 1943 in a neo-Romanesque style.

The church is still part of the Shelter Home for the Elderly (IRA) and is

now officiated by the Romanian catholic community.

On the night of the 24th/25th of October 1993 several works of art were

stolen from this church. One of them, Christ at the Column,

attributed to Palma Giovane, was recovered in June 2014. In September 2017

there was much scaffolding and ongoing building work converting the

complex for use by the university.

|

|

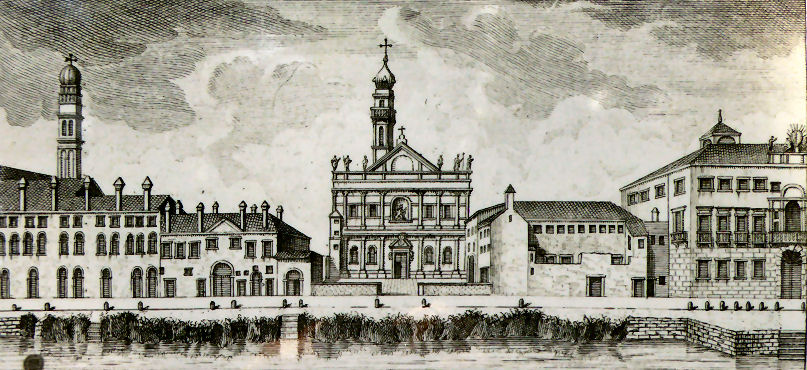

History History

Tradition puts a church here as early as the 4th century, but a documented

mention of a church built over a

necropolis is dated to the 9th March 1147, with monks from a Benedictine Monastery

officiating here from 1177. That complex had become seriously dilapidated by the 16th

century, but it wasn't until the years 1657-66 that the church was rebuilt

to an aisleless Latin cross plan to plans by Vincenzo Scamozzi. In 1671

Cardinal Gregorio Barbarigo found the church completed with five altars,

one housing the bodies of the martyr Saints Pauline and Valeria. In 1738

the building was enlarged towards the facade. With the Napoleonic

suppressions the church passed to the parish and the monastery abandoned

until it became a girls' boarding school in 1818. The bodies of Blessed

Pellegrino and Blessed Ongarello were brought here, but did little to

improve the church's popularity. The church was closed to worship is art

moved to the Immacolata church. Ognissanti reopened as a parish church on

July 5th 1941.

Interior

Contains three altarpieces from the 17th and 18th century and some early frescoes,

notably a fragment depicting Christ Pantocrator to the right of the high altar and a

Byzantine-style lunette.

Ruota degli

esposti

Inside the

doorway to the monastery, to the side of the church, is still to be found

a ruota degli esposti, a turntable in the wall for the depositing

of unwanted babies, which was still in use in the early 20th century.

Opening times

Just for services, it seems.

|

|

Eremitani

Piazza Eremitani |

|

this church now has its own page

|

|

Immacolata

Via Belzoni |

History

The Church of St Mary

Immaculate was designed by A. Tosini in 1853, being built over the site of

an earlier church called Santa Maria Iconia. The first documented mention

of this earlier church dates to 1165.

It became a Templar church and with the

order's suppression, a parish church for a little while, until 1312 when the

Knights of Malta (re?)acquired it until 1807, when it was bought by one Luigi Gaudio who converted

it for 'other uses'. It was demolished by 1834. The

unusual naming of the Virgin Iconia seems to derive from the word

cuneus, meaning a narrow plot of land by two rivers.

Interior

Contains much art from other churches, mostly the nearby Ognissanti,

including the Virgin of the Boatmen, a 15th century wooden statue, and

works by painter Gaspare Diziani - Job mocked by his wife, The

Killing of Agar, The Expulsion of Eliodoro, Gideon's Miracle, and

The Robe of St. Joseph shown to Jacob, Agar and Samuel. Also two

paintings by Francesco Maffei (Saint John in Patmos and a

Crucifixion from Ognissanti), an Assumption by Santo

Peranda, and an altarpiece depicting the Virgin and Saints Mauro and

Agnes by Bonifacio de 'Pitati.

Lost art

The earlier church had an Assumption with Apostles by Palma Giovane

over the high altar, a Baptism of Christ by Veronese (from San

Giovanni alle Navi) over the right hand one, and a Deposition by

Pietro Damini on the left.

|

|

San Benedetto Vecchio

Riviera San Benedetto |

|

History

Built in 1195 by Giordano

Forzaté for White Benedictines (so called because of their light-coloured

cowls). It initially housed men and women but arguments over the

management of finances led to the bishop splitting them up in 1259, with

the nuns remaining here and the monks moving to

San Benedetto Novello,

completed in 1262. The convent then flourished. Between 1356 and 1397 the

abbess was Orsola Buzzacarini, who took the name Anna when she became a

nun. She was the elder sister of Fina Buzzacarini, who was the wife of Francesco

I da Carrara (called il

Vecchio) and the commissioner of Giusto's frescoes in the

Baptistery. Anna embellished the convent much, with donations of

altarpieces and the like from her wealthy relatives, including many

endowments from Fina -

the construction and decoration of the

chapel of Saint Louis of Toulouse here being the most celebrated, gifts of

rich clothing and fabric the most common, paying for a wall to be built

the most prosaic.

Later Caterina Cornaro was

educated here, until the age of fourteen.

Much work from 1612, including a realignment and a new façade, at the

behest of abbess Aurora da Camposampiero, probably

as a result of the reforms of the Council of Trent. The old Romanesque

façade can still be seen at the west end.

The convent was

suppressed by Napoleon in 1810 and converted into a military barracks, the

church passing to parish use. Early 20th century restorations, but bombing on 11th March 1944

(the same raid by American bombers, targeting the marshalling yard, which

destroyed most of Mantegna's frescoes in the Eremitani) caused much

damage and destroyed many works of art, including the Apocalypse

cycle by Giusto de'Menabuoi and the chapel of Saint Louis of Toulouse,

rebuilt in 1952. There was also post-war restoration of the interior back to Romanesque style.

Giustiniana Wynne is buried here. She being

the Venetian-born daughter of an English duke and a writer, famous for her

friendships with Casanova and (more scandalously) Andrea Memmo. Her life

and affair with the latter being the subject of Andrea Di Robilant's book

A Venetian

Affair.

Exterior

The 18th-century façade has two bas reliefs of Saint Benedict, with statues of the

patron saints of Padua along the top.

Interior

Big, boxy and dark - there are small

clerestory windows on the left only - with plain brick walls and stout

pillars dividing the nave from the aisles. Pitched timber roof. Huge

well-populated baroque altar at the end of the choir, which is just a

continuation of the nave.

In the centre of right hand wall is an altar containing the remains of

Giordano Forzaté with an altarpiece celebrating him by Alessandro Varotari.

A putto in this painting carries a model of the church before the new

façade of the 17th century.

The door in the back wall leads to a chapel

frescoed in the 18th century which has a painting of Christ Among the

Saints by Domenico Tintoretto, the son. Works by Maganza, Minorello,

Balestra, Zanchi and Damini. Various frescoes by the door, including a 13th

century Romanesque one of The Deposition.

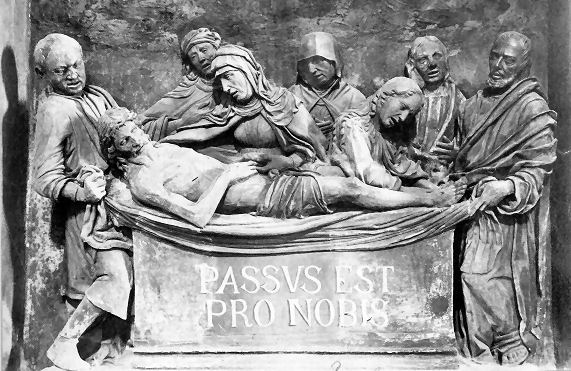

Lost art

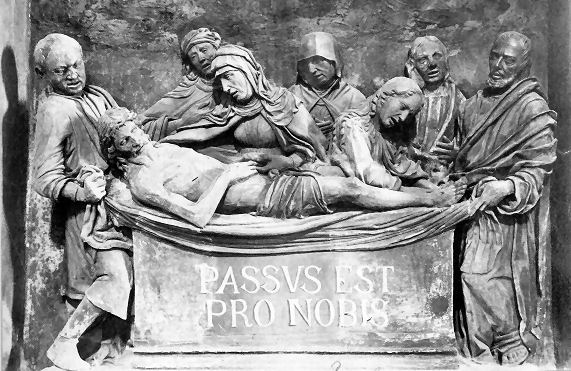

In addition to the

Apocalypse cycle by Giusto de'Menabuoi the bombing on 11th March 1944

also destroyed the renaissance terracotta Deposition group in the

photo below. Only fragments remain in the Diocesan Museum.

Famous legend

The stick which

Giordano Forzaté used to

mark out the boundaries of the monastery is said to have miraculously grown

into a tree when planted in what became the cloister adjoining the right

aisle of the church. It's fruit was said to cure fevers and it

supposedly reacted badly to deaths amongst the nuns and descendents of the

founder. After the suppression of the monastery the tree was transplanted

to the garden of the Palazzo Capodilista where it still thrives, we are

told.

|

|

After the bombing of

March 11th 1944 |

|

San Benedetto Novello

Riviera San Benedetto |

|

San

Bonaventura delle Eremite

Via Alberto Cavalletto |

History

Monastery built by monks

moving from San Benedetto Vecchio in 1262 (see San Benedetto Vecchio entry

above).

Consecrated

on March 6th 1267. Went into decline in the 15th century. In 1441 Pope

Eugene IV gave it to another order, who improved it and in 1442 sold it to

the Olivetans who rebuilt the cloisters in 1504 and the church in 1567, to

designs by Francesco da Trevigi. The Olivetans thrived, until they were

expelled by the Venetian republic in 1797. Suppressed in 1810. Nuns moved

back in in the late 19th century, with the church being restored and

rededicated in 1894.

Lost art

Saint Frances of Rome Restores the Sight of a Girl by Palma Giovane

is in Eremitani Civic Museum. As is

Saint Bernard Tolomei Helps the Infected by Domenico Maria Canuti,

a Bolognese artist. And another one where the same saint helps the

demon-afflicted. They are the two surviving panels from a cycle depicting

the life of this saint created by the artist for this church between 1663

and 1664. |

|

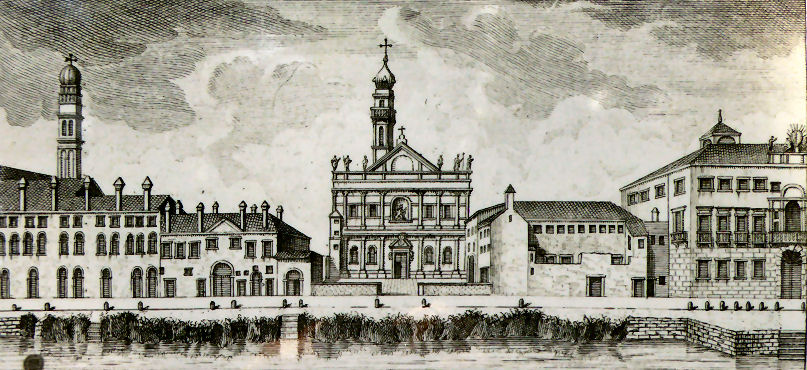

History History

Part of a complex built in the late 17th century. The order of the Virgin

Franciscan Hermits in Padua was founded on August 10th 1612 by Sister Graziosa Zechini and was first located in

the Pontecorvo area in three houses

donated by Lucia Noventa, a wealthy widow. In 1615 the

first chapel was built there. Noise and harassment, due to their proximity

to two taverns, resulted in the order moving here, onto land provided by

the patrician Malipiero family, purchased on February 26th 1680 with the

approval of the bishop Gregorio Barbarigo. The community moved here on

11th May 1682 , with the church completed later, the first mass being sung

on the 19th of March 1688. The complex survived the Napoleonic and Savoy

suppressions, with no electricity until

1985.

The church

Baroque

facade with four Doric pilasters supporting a pediment unusually

containing, we are told, a thermal window. Over the door is a niche

containing a statue of St. Bonaventure with the inscription SAN

BONAVENTURA / AN. DO. MDCXCIII / ANTONIO ZANINI DETTO MANGRANDA / FECIT DI

ANNI XVIII

Campanile

Odd in having a belfry of four high arches.

Interior

The seventeenth-century

interior is characterized by vertical momentum, we are told. Over the high

altar is St. Francis, St. Anthony, St. Bonaventure and St. Peter of

Alcantara by Gaspare Diziani . On the side altars, to the right a

Holy Family with Saints Zachary and Elizabeth by Pietro Damini, to the

left an Immacolata by the circle of Francesco Zanella.

Opening times

Online sources say hardly ever. A sign on the door said 3.30-6.00

every day, but it wasn't open when I passed in hope on evenings in May 2016 and

September 2017.

|

|

San Canziano

Piazza delle Erbe |

History

Named for Saints Cantius, Cantianus, and Cantianilla, the martyrs of

Aquileia, this church was already standing in 1034 as part of the monastery of Santo Stefano.

Damaged by earthquake in 1117 and fire in 1174. This original church with

three naves and an apse oriented to the east was rebuilt between 1595 and

1617, thanks to the legacy of Don Cesare Mantova, parish priest for 27

years. The completion of this work saw the presbytery now on the south

side and the construction of a new facade overlooking Piazza delle Erbe.

The church was finally consecrated on October 24th 1757 by Bishop

Alessandro Papafava. Restoration in 1955.

The church

Down the right side details and the rose window of the original facade

are visible. The current facade, once attributed to Palladio is now

thought to be the work of Vincenzo Dotto and Giambattista della Sala, The

niches between the two pairs of Corinthian semi-columns have statues of Purity and Humility by Antonio Bonazza.

Above are two 18th century bas-reliefs depicting the trial and martyrdom

of the church's name saints. On the attic level are statues of the four

Evangelists by Pietro Danieletti. In the middle of the façade is a

weather-damaged fresco of the Immaculate Conception by Guy Louis Vernansal.

Interior

A nave with a pair of aisles, or arguably an aisleless space with two

central side chapels each flanked by tapering functional spaces. Contains

works from the 17th century: terracotta statues of saints flanking the

altar in pairs of niches, by Paduan sculptor Andrea Riccio, including

Saints Anna, Cantianus, Cantianilla (or Agnes) and Jerome. Unstriking

paintings include The Procession of Carlo Borromeo by Giovanni

Battista Bissoni and Pietro Damini's The Miracle of Saint Anthony and the Miser's

Heart, in which the surgeon is a portrait of anatomist and surgeon

Girolamo Fabrici d'Acquapendente. The high altarpiece is a Virgin and

Saints attributed to Padovanino. These are

all mostly not well lit. Under the left hand altar, now dedicated to Saint

Rita, is a polychrome terracotta statue of the Dead Christ, another

work by

Andrea Riccio from 1530. His real name was Andrea Briosco, but he is

now known by his nickname Riccio, which means curly.

Lost art

Two polychrome terracotta busts depicting Mary Weeping from a

now-fragmentary 1530 Lamentation group by Andrea Riccio

are in the Eremetani Civic Museum.

Opening times

Monday to Saturday 7.30-13.30

Sunday 19.15-21.00

|

San Clemente

Piazza dei Signori |

|

History History

A church on this site dates back to the end of the 12th century - a document of 1190

mentions its elevation to a parish church. It underwent much rebuilding in

the 16th century when the piazza outside was reorganised, and in the 17th and

18th centuries. It's the burial place of Tiziano

Minio, a famous Paduan sculptor.

Façade

Statues of Saints Giles and John the Baptist from

1696 in the niches, Daniel, Clement and Justina on the tympanum.

Interior

A single nave with a small square apse. Paintings of the 17th and 18th

century by

Giovanni Battista Bissoni, Pietro Damiani (Jesus Giving the Keys to Saint

Peter) Giulio Cirello (Prodigio dell'Acqua di San Clemente)

Pietro Malombra (Saint John the Baptist in Glory with Saints Carlo

Borromeo and Francis) and Luca Ferrari. The high altar (1782) has an altarpiece of

Pope Clement I (Saint Clement) Surrounded by Angels by Luca Ferrari. The

Altar of St Anthony erected by the Guild of

Grocers (The Fratelea Casolinorum) has a bas relief of Saint John the Baptist holding the tools of their trade.

The fresco fragment of The Virgin and Child (see right)

on rear wall under organ gallery near the entrance is attributed to Jacopo Bellini.

Lost art

A damaged sculpted panel of the Miracalo di Sant'Alò by

Nicolò Baroncelli is in the Eremitani Civic Museum.

Opening times

9.00-1200, 4.00-6.00

supposedly, but I have only found it open once in

three years/tries.

|

|

San Daniele

Via Umberto I |

History

A church and monastery were built in 1076. Legend has it that when the body of Saint

Daniel, the early Christian martyr and one of Padua's patron saints, was

bring translated from the church of Santa Giustina to the Cathedral when

they got here the relics became too heavy to carry, with a darkness and

thunder and lightning to force home the point, so the bishop built a

church here to house them. Not much of this original

chapel remains as it was almost completely rebuilt in the 18th century in

late-Baroque style by Francesco Muttoni with more work on the façade and

interior, neo-classical this time, in the 19th century. In 1771 the

monastery was suppressed and became a private residence, but in 1948

Benedictine monks, exiled from a monastery in the former Yugoslavia, came

here.

Façade

The façade is by Agostini Rinaldi with statues of local Saints Daniel and

Justina,

by Francesco Rizzi, in the niches.

Interior

Hall-like with an organ loft over the entrance. The shape of the apse

derives from the romanesque church. The ceiling has 19th

century Scenes From the Life of Saint Daniel by Sebastiano Santi. A

Nativity altarpiece by Palma Giovane is reported.

The

Paduan illuminator Benedetto Bordon (c.1455-1530) is buried here.

Lost art

A 1795 guide to Padua by Pietro

Brandolese mentions the first altarpiece on the left as depicting

St Charles Ministering to Plague Victims by Giovanni Battista

Bissoni, and an altarpiece on the right having a canvas depicting The

Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John the Baptist by Francesco

Zanella.

|

|

San Francesco Grande

Via San Francesco |

History

Designated as Grande to avoid confusion with the church of San Francesco

Piccolo, a church demolished by the 16th century, this church was built by Baldo Bonafario of Piombino and his wife Sibilla de Catto, along with

a convent hospital, for the Franciscans. Work began in

1414 led by builder Nicholas Gobbo. In 1417 the church was built and work

continued until mid-century. After the death of Bonafario the work

was completed by his wife. This church was a single nave with chapels on

the left and was consecrated on October 24th 1430. Due to the growing

popularity of the Observant Friars Minori the church and monastery were enlarged at

the beginning of the 16th century, under the direction of architect Lorenzo Pardi da Bologna.

The chapels on the right were built and and the transept enlarged. The

monastery was enlarged too, with a second cloister added. Fresco lunettes in the style of Squarcione

in the loggia on the façade are very faded but were recently restored.

Baldo and his wife Sibilla were buried here, as were Ferdinando Carlo

Gonzaga-Nevers, the last Duke of Mantua, and Francesco Squarcione, a

painter more famous for his pupils, including Mantegna, Zoppo and Crivelli,

than his own talents.

Suppressed in April 1810, becoming a parish church in the same

year. In 1862 the floor was re-laid at the expense of many old tombstones.

Total restoration in 1873. In 1914 the Franciscans returned to the church

and part of the old convent.

Interior

Four side chapels each side of the wide nave with wide aisles, the transept not much

deeper than the chapels but the right hand chapels are deeper and the

right hand transept arm is marble-fenced off to enclose a red and

white marble baroque extravagance by Giuseppe Sardi, built 1655/70.

A long choir with an

arch-shaped fresco of The Annunciation over the arch (see

below right).

The second chapel on the right is impressively frescoed inside

(see below) and into the vault and over the arches of the

aisle space in front,

in 1523 by Girolamo dal Santo.

An Ascension by Paolo Veronese originally to be found in the marble frame

in the left transept chapel is now on the entrance wall high over the door

(see right). The lower part with the Apostles was added in March 1625 by Pietro Damini

after this part of the original was chopped off and stolen. The

inscription inserted at the Fathers' request speaks of a 'nefarious theft

from the highly wrought painting of the excellent Paolo Veronese' being

restored by 'the felicitous pencil of Pietro Damino'. The Twelve

Apostles in Prague's Olomouc Gallery is now thought to be the lost

lower part. The parts were exhibited together at the Veronese e Padova exhibition

in Padua in 2014. But another Assumption, in Dijon, is also a

candidate for the top of the Prague painting, which they call Eleven

Apostles.

|

|

|

|

The Scuola della Carità

|

History

Opposite San Francesco Grande, this scuola was founded in 1414 for a lay confraternity, also using

bequests from Baldo Bonafario and his wife Sibilla.

Interior

The scuola houses

a cycle of 12 fresco panels of episodes from

The Life of the Virgin made by Dario Varotari in 1579. It's an unusual

sequence in that it avoids the usual scenes involving the life of Jesus.

The panel in the photo (right)

is the rarely-seen Death of Saint Joseph, a subject which became

more popular in the 17th century.

Opened by volunteers from Salvalarte, who don't have a website but are a

branch of Legambiente.

Scuola

Opening times

Thu & Sat 10.00-12.00

Thu-Sat 4.00-6.00*

(*May-October 4.30-6.30)

|

|

|

|

San Gaetano

Via Altinate |

History

Also

known as Santi Simone e Giuda this church was built from 1582 to 1586 by Vincenzo

Scamozzi for the Theatines, an order founded by Saint Cajetan of Thiene, on the site of an

old church called Saint Francesco Piccolo run by the Umiliati from whom

the convent complex had passed when their order was suppressed by the Pope in 1571.

Between 1578 and 1581 the Theatines had bought up more property, with the help

of Bishop Federico Cornaro and with money from Alvise Cornaro. But

the expansion work from 1629 failed to respect Scamozzi's plans, and baroque

enrichments carried out at the behest of provost Raffaele Savonarola

between 1692 and 1730 did not find universal approval. This work involved

marble enrichments, three new altars and mannerist paintings. Suppressed

by Napoleon in 1810, part of the monastery became the Palace of Justice in

1844 and the church became a parish church. Restoration in the 19th

century. A fire which almost destroyed the monastery in 1929 left the

church undamaged.

The monastery is now a museum.

Interior

This was the first

centrally-planned church built in Padua . Inside it's aisleless tall and octagonal (or maybe

square with the corners chopped off) and decorated with the marble panels

and stucco typical of the 18th century. Sharp left as you enter, and down

some stairs, is the unserene Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre. The small Presbytery and separate

choir beyond are all marble and stucco too, but the large sacristy is much

plainer and more solemn. . Inside it's aisleless tall and octagonal (or maybe

square with the corners chopped off) and decorated with the marble panels

and stucco typical of the 18th century. Sharp left as you enter, and down

some stairs, is the unserene Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre. The small Presbytery and separate

choir beyond are all marble and stucco too, but the large sacristy is much

plainer and more solemn.

Art highlights

The dome has sixteen radiating trompe l'oeil fresco panels of Paradise

by Parisian painter Guy-Louis Vernansal. Paintings include an oddly bright

Deposition/Mourning by Varotari.

A subtly mobile statue of the Virgin and Child

is a survival from the Umiliati church by the Paduan sculptor Andrea

Riccio (1470-1534) (see right). His real name was Andrea Briosco,

but his nickname, Riccio, means curly.

Two side chapels the right-hand

one has The Transfiguration by Pietro Damini, The Presentation

at the Temple of 1610 by Palma Giovane, is in the left-hand one.

There's San Carlo Borromeo

Saving a Child by Pietro Damini and works by Jacopo Bassano, Alessandro

Maganza and GB Bissoni. There's an altarpiece by Vernansal too, depicting

The Flagellation, in the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre.

Opening times

9.00-12.00, 4.00-6.00

|

|

|

|

San Giovanni di Verdara

Via San Giovanni di Verdara |

History

The church of a monastery built in the early13th century by Benedictine

monks, in an area know for the lushness of its vegetation, hence the

name. In 1431 Pope Eugene IV gave the complex to his nephew Cardinal

Antonio Correr , bishop of Ostia, who entrusted it in 1436 to a community

of Lateran Canons who undertook a campaign of restoration and enlargement,

entrusting the work to Lorenzo da Bologna and Giuliano da Porlezza. From

the 15th to the 17th century the canons collected art and books, amassing a

library that attracted the likes of Pietro Bembo. The collection of Marco Mantova

Benavides, a renowned 16th century humanist, jurist and collector who is

buried in the Ermitani, came here in 1711. In 1783 the Venetian Republic

abolished the order of the Lateran Canons. The art went to the civic

museum and the books to the Marciana Library. The church remained in use

with the monastery serving as an orphanage, an Austrian barracks in 1847.

The church was last used by Jesuits in 1866, and the complex now houses

the Military Department of Forensic Medicine of Padua, the church remaining as a neglected and

inaccessible wreck.

People buried in the church: sculptor Andrea Briosco, humanist and writer

Lazarus Bonamico, Calfurnio Giovanni, medallist Giovanni da Cavino,

painter Luca Ferrari, and Domenico Senno.

Exterior

Has a largely 14th/15th century Gothic facade with a large rose window and

later embellishments. On the arch above the main door was a fresco by Giacomo Ceruti of the Virgin with Saints Joseph and John,

while to the left was the tomb of Andrea Briosco bearing the artist's

effigy, dispersed after 1797. To the south are a pair of large cloisters.

Interior

A nave and two aisles.

Lost art

A 1622 Wedding at Cana by Padovanino,

now in the Chapter Hall of

The Scuola di San Marco in Venice.

On the altar of St. Patrick, the first on the

left, was Giambattista Tiepolo's Miracle of Saint Patrick of 1745/6 now at

the Eremitani Civic Museum. There they used to call it Saint Paulinus of Aquileia, and

there was controversy over whether it depicts the Bishop of Ireland or the

latter

more local, if obscure, saint. The Lateran Canons' particular devotion to

Saint Patrick was cited. Now the caption says it's Saint Patrick Bishop

of Ireland. Two works by Pietro Rotari where commissioned at the same

time.

Also there from here is a late Supper at Emmaus by

Giambattista Piazzetta and a large Crucifixion panel by Stefano dell'Azare.

|

|

|

|

San Luca Evangelista

Via XX Settembre |

History

A church dedicated to the Twelve Apostles was built in 1174, replacing an older building

which had been demolished to make way for the city walls. This building was

itself demolished by order of James I of Carrara in 1320, after which construction of the current church

began, consecrated on

the 18th of

October 1381. In the 17th and 18th century rebuilding altered the original

east-west orientation. Suppressed in 1807 by Napoleon, on July 2nd 1815 the church was reopened as

part of the new parish of Santa Maria dei Servi. It is currently used by

the Greek-catholic community.

The church was the seat of the Confraternita

dei Pittori.

On May 6th 1655 Bartolomeo Cristofori was baptized here, he being the

inventor of the piano.

The church

The building is now oriented north-south, but you can still read the

original east-west orientation of the external walls. The simple baroque facade,

with two Ionic pilasters on each side, overlooks a fenced area which used

to be a cemetery. The facade is topped with statues of the Virgin (at

the top) St. Anthony (left) and St. Francis (right). On the wall are two plaques.

One commemorates the reopening of the church in 1815, the

other the baptism here of Bartolomeo Cristofori .

Interior

The below is all what I've read, not what I've seen.

A Greek cross, the only one so shaped remaining in Padua. The

side chapels were added in 1834. To the left, there was a painting of Sant'Espedito Martyr,

which was stolen in 1997 and now replaced by a photo.

Over the baroque 18th century altar in

the chapel on the left is a 14th century fresco of The Virgin and

Child, rediscovered during rebuilding in 1778 and restored by

Francesco Zanon, and again restored in 1998, previously described as "in

the manner of Giotto" and now attributed to Giusto de 'Menabuoi.

Worryingly it is reported that the figures

were crowned with silver tiaras donated in 1995.

Further along on the left is a Pieta attributed to Bartolomeo Montagna.

In the north transept is a 17th century painting of the Veronese school

showing depicting Saint Benedict Handing his Monastic Rule to Saint

Augustine.

The marble high marble altar, decorated

with semiprecious stones, is by Francesco Corbarelli and dates to 1667-68.

The decoration and art here is all 17th century. The high altarpiece by Pietro Damini San Luca

of The Virgin and the Patron Saints of

Padua in which the Torlonga

is also depicted. |

|

San

Michele

Oratory -

Piazzetta San Michele |

History

The original church here may date back to the 6th or 7th

century,

being dedicated to the Archangels. Or it could be later as the first

documented mention dates to 970. The Carrara lords helped in its

rebuilding after a fire in 1390, which was caused by fighting between

Francesco Novello's Paduans and Milanese soldiers, sent by the Visconti,

who had besieged the nearby castle. This work, which involved expansion

and painted decoration, was finished in 1397. In 1497 it passed to the

congregation of Santo Spirito in Venice, in whose hands it remained until

suppressed by the Pope Alexander VII in 1656. The Venetian Republic sold

of its assets to pay for its war against the Ottoman Empire. After

becoming the property of the Patriarch of Aquila the church went through

the hands of various Venetian families in the 16th and 17th centuries. In

1792 much of the contents and art were removed, in 1808 it ceased to be

the parish church and in 1812 it was closed. In 1815 Francesco Pisani, who

lived in the palazzo next door, decided to demolish the church. All that

was left was part of the nave and the chapel dedicated to the Virgin,

which took on its present name at this time.

Andrea Palladio was baptised in this church in 1508.

Interior

The current small space, once the chapel mentioned above, is full of

vivid frescoes by Jacopo da Verona, a pupil of Altichiero. They were painted in

1397 and depict the Life of the Virgin, having been

commissioned by Pietro de' Bovi, an official of the Ferrarasi mint.

Opposite the entrance, above the arch into the nave of the church, is a

three-panelled Annunciation. Below is Saint Michael, weighing

the souls of the dead, and The Banishment of Adam and Eve, possibly

a 16th century addition.

On the left wall are a Nativity and The Adoration of the Magi,

the latter containing portraits of the Carrara lords Francesco il

Vecchio, Francesco Novello and Francesco III as the first, second and

third magi. Higher up to the right the Torlonga is depicted, it being one of the

towers of the old castle before its 18th century transformation into an

observatory.

The right wall has The Funeral of the Virgin and The Pentecost

(see right), the former panel containing portraits of the

commissioners of the frescoes, to the right dressed in dark robes. The wall of the

current entrance has a very damaged Ascension. Under the arch, into

what's left of the church, are The Doctors of the Church and The

Four Evangelists. Some of the 16th century frescoes which decorated

the nave remain, including a Deposition and a St Paul, attributed to

Stefan dell'Azare and Domenico Campagnola respectively. When I visited

in May 2016 this area was being restored, or maybe rebuilt.

Lost art

A large damaged fresco fragment of the Virgin of Humility

with Saints James and Anthony Abbot probably by Cennino Cennini from

around 1398/1400, now in the Eremitani Civic Museum, is said to have come

from the vicinity of this oratory.

Opening hours

Tuesday-Friday 10:00 - 13:00

Saturday and Sunday 16:00 - 19:00 June to September

15: 00-18: 00 October to May

Entry: full price €3.00, reductions €2.50

Run by the the

Torlonga

association who also run the Specola Museum over the river.

|

|

|

|

San Nicolò

Via San Nicolò |

|

History

Original church built 1090 by Bishop Milo. The oldest parts of the

current church are the door and the columns near it, from the 14th

century rebuilding. The rest is much later, 17th and 18th century, but

retains an ancient feel.

This may be because the church underwent much restoration in the

1960s/70s laudably aiming to restore it to it's pre-baroque state.

Exterior

The area in front of the church was a cemetery before Napoleon. The

asymmetry of the interior is reflected in the facade view, with the

Forzatè chapel poking out to the right of the campanile. Over the 15th

century doorway is a sculpted figure of Saint Nicholas, with God above and

an Annunciation to the sides.

Interior

Has Padua's common alternating columns-and-pillars thing separating the nave from a

narrow aisle on the left and an aisle and three connected deep chapels on

right.

A large and Giottoish 14th-century fresco fragment dominates the

beginning of the left aisle depicting The Crucifixion with scenes

from The Life of John the Baptist above (see below right). These are by Gerardino da

Reggio and commissioned in 1374 by Marcus Forzatè, whose family chapel is

opposite. There is a very damaged frescoed vault above with four roundels

probably of the Four Evangelists.

The decorated ceiling in the shallow chapel

to the left of the choir depicts Saint Liberalis and is said to be by Jacopo da Montagnana

(Jacopo Parisato) a pupil of Mantegna. The high altar was converted from

the old Baroque altar table. The choir

semi-dome is frescoed and there's an Annunciation frescoed over the

right-hand chapel.

Of the right hand chapels the furthest, the

organ chapel, has Il Compiano by Varotari.

The middle,

confession, chapel has a very nice Virgin and Child with Saints

Francesca Romana and Eurosia of 1777 by

Giandomenico Tiepolo (the son) (see photo right) formerly in the

church of

Sant'Agnese. Before the 1960s

renovations this painting was over the high altar.

The first chapel,

the baptistery, has a triptych of

Virgin and Child with Saints James and Leonard described as 'school of Bellini'.

It sits on the rosso Verona marble monument to Giordano and Marco Forzatè.

The former was a Benedictine and a monastic reformer as well as coming

from one of the dominant local feudal families. That the family later

intermarried with the Carrara possibly helps explain Giordano's later

becoming know as beato. He is buried in

San Benedetto Vecchio.

On the church's back wall, to the left of the door, is Saint

Agnes in Glory

recently restored.

An exceptional polychromed terracotta statue of the Virgin and Child Enthroned,

c. 1468–70, by Giovanni de Fondulis.

Campanile

Restored in the 19th century.

Lost art

Ten panels that made up a polyptych of 1456-8 by Giorgio Schiavone (real

name Juraj Čulinović) are now in the National Gallery in London. Called

The San Niccolò Altarpiece it was probably made for the chapel

of Giovanni di Roberti in this church, later inherited by the

Frigimelinca family. The central panel of the

Virgin and Child is flanked by full and half-length panels depicting

saints and a Pietà. The artist signed his name on a creased

cartellino on the front of the Virgin’s throne - 'the work of Sclavoni,

Squarcione’s pupil’.

|

|

|

|

San Pietro Apostolo

Via San Pietro |

History

A church was known to have existed here in

the 4th century, a rebuilding of 1026 followed destruction by Hun invaders

around 900, and saw it passing to Benedictine nuns. Enlarged in the 14th

century, substantial work in the 18th century and heavy restoration in the 19th and

20th centuries.

Following the Napoleonic suppressions of 1809 the nuns remained for a few

years and monks from

San Prosdocimo came here too, bringing

with them the body of Saint Eustochium,

which is

still here.

Interior

Has the appearance of being aisleless but the aisles are behind a wall on

the left and doors on the right. The nave has two pairs of shallow plain

side altars. The deep choir is a riot of dark but well-illuminated fresco

decoration. The longer and higher enclosed left- hand aisle is dedicated to

Saint Eustochium and has her remains and a fresco-decorated ceiling. The

right-hand aisle has two spaces that are more like chapels.

Art highlights

A painted altarpiece by Varotari (or Campagnola) of

The Giving of the Keys, which is over the high altar, and Palma Giovane's

The Fall of Saint Paul (see below left) which is over the second altar on the left.

A polychromed terracotta relief, with a painted background, depicting The Lamentation, c.1480–90, by the circle of Bartolomeo Bellano,

a Paduan student of Donatello.

Lost art

The rather fine 1447 San Pietro Polyptych by Francesco de'Franceschi is now in the Eremitani Civic Museum - all twelve

panels, but without the original frame. Not much is known about this

artist but he may have collaborated with Antonio Vivarini in Venice.

The (unusually round) floor tomb stone of Antonio and Catharina Maggi da

Bassano (see below right), a celebrated jurist and his wife, from this church, possibly

installed in front of the high altar, is now in the V&A in London. It was

made in 1520 by Vincenzo and Gian Matteo Grandi. The square space in the

middle may once have contained an engraved brass panel.

In January 2021 Laura Jacobus (who wrote the book on the Scrovegni Chapel)

gave an online lecture for Birkbeck College in London on the little Giusto

de' Menabuoi Coronation of the Virgin triptych in the National

Gallery. In it she put forward the theory that the work was made for a

young woman entering a convent, specifically the Benedictine convent here,

and further that she could have been a younger daughter of the Scrovegni

family, who had connections here and with the nearby San Nicolò complex.

She admitted that the theory is speculative, to say the least, but it is

tempting too.

Opening times

9.00-12.00 Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday

|

|

San Prosdocimo

Via San Prosdocimo |

History

A church with medieval origins and named for Saint Prosdocimus,

the first bishop of Padua from the 4th century. Also known as the Duomo dei Militari,

formerly the church of a monastery of Benedictine nuns, following

Napoleonic suppression it was used as an army bakery and warehouse.

Following restoration work it became a parish church for the military.

After the earthquake of the 3rd of June 2012 the church was declared

unsafe and closed, but following restoration work it was officially

reopened on November 5th 2019 - the façade now looking much better than it

did when I took the photo in 2017.

Lost art

Giambattista Tiepolo painted an altarpiece showing Saint

Joseph with the Infant Jesus and Saints Francis of Paola, Anne, Anthony,

and Peter of Alcantara (see left) for this church in c.

1730/35. It's now in the Accademia in Venice.

|

|

San Tomaso

Becket

Via San Tomaso |

|

Sant'Alberto Magno

Via Guglielmo Marconi |

|

History

Baroque, built in the 17th century on the

site of earlier churches. Until 1890 it was run by the secular priests of

San Filippo Neri.

Interior

Inside are said to be works by A. Bonazza, Bonaccorsi, Ferrari, Pellizzari,

Francesco Maffei and a Crucifix attributed to Donatello. The ceiling has

fifteen

canvases from the 17th and 18th centuries depicting the Mysteries of the

Rosary.

The church also has a collection of more than a

thousand relics, including the heart of Filippo Neri and a portrait of him

which sweated twenty-seven times in 1632.

The sacristy houses the Museo di San Tommaso Becket, founded in 1966, which has

medieval frescoes, fabrics, liturgical furnishings, manuscripts,

archaeological items, goldsmiths work and paintings, including a

Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints from the mid-1440s by Antonio Vivarini

and Giovanni d'Alemagna, from an altarpiece made for the church of San

Moisè in Venice. (See Lost art below.)

The church features in the Italian TV series Don

Matteo, about a crime-solving priest from Gubbio, that has run to 12

seasons.

Lost art

Two panels, depicting Saints Peter and Jerome and Saints Francis

and Mark which flanked the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints

by Antonio Vivarini and Giovanni d'Alemagna mentioned above are in the

National Gallery in London.

Opening times

At the whim of the parish

|

|

|

|

Sant'Agnese

Via Dante |

History

A church is said to been here in the 12th century. First documented in

1202 as a parish church. This 13th century structure underwent

restoration and expansion from the early 16th century, retaining its

single-nave interior. After Napoleon the church lost its parish status and

was later passed to the missionary Fathers of the Sacred Heart who lived

here until 1939.

It fell out of use during the Second World War and on October 7, 1948 was

deconsecrated. It's art was moved to San Nicolò and the Episcopal Palace and the building

was sold and later made into a garage, which it remained until the late

1990s. A portico was removed in the 20th century. Now abandoned and

falling down, it was sold in 2011 to be converted to flats, but not much

progress has been made, the scaffolding and graffiti visible in the photo

having been there now for several years.

The facade with renaissance doorway by Giovanni Maria Mosca -

oriented to the east - was probably covered in fresco in the 16th century.

Interior The interior has been gutted.

Campanile A Romanesque bell tower of the 13th century.

Lost art

Paintings by Francesco Minorello, a pupil of Luca Ferrari, depicting the life of Saint Agnes (St

Agnes refusing Gifts and the Martyrdom of Sant'Agnese at the

Gallows) are now in the Episcopal Palace.

Over other altars were works by Giulio Cirello, another pupil of Ferrari - St Agnes

Urged to Marry the Son of the Prophet (aka St Agnes Beaten by the

Roman Prefect) (see left) and St Martha as a Nun Sprays Holy Water on a Dragon. The former, at least, is

also in the Episcopal Palace, and was restored in 2000.

An altarpiece of 1777 by Giandomenico Tiepolo of the

Virgin and Child with Saints Francesca Romana and Eurosia, formerly

on the first altar on the right, is now in

San Niccolò.

|

Sant'Andrea

Via Sant'Andrea |

History

Dedicated to Saint Andrew the Apostle, the original church here was

built before 1130 and in 1640 was completely rebuilt. In 1875 the single

nave was transformed into a nave and aisles separated by Corinthian

columns, with decoration reflecting contemporary taste. The work was

finished in 1884 and the 'unfashionable' art previously in the church was

dispersed. Some restoration in the 1920s, the church was consecrated on

October 17th 1941. Paduan Arrigo Boito, writer of libretti for

Verdi and lover of Eleonora Duse, was baptized here on 19 March 1842. The

building was damaged by the earthquake of the 3rd of June 2012.

Interior

The ceiling is decorated with paintings by Antonio Grinzato, but

before the 19th century interventions showed The Apotheosis of

St. Andrew by Giambattista Mengardi . The apse has an altar taken from

the demolished church of San Marco which has three marble panels - The

Sacrifice of Isaac, The Supper at Emmaus and The Paschal Lamb -

by Francesco Bonazza. An altarpiece depicting the Virgin and Child

with Saint Andrew by Giovan Pietro Possenti. In the aisles and over the

side altars are works from various sources and periods, including Saint

Francis Xavier by Natale Plache, from the Gesuiti church demolished

in the late 18th century and a Saint Martin in Glory of the 17th

century, once the high altarpiece of the church of San Martino. the aisles and over the

side altars are works from various sources and periods, including Saint

Francis Xavier by Natale Plache, from the Gesuiti church demolished

in the late 18th century and a Saint Martin in Glory of the 17th

century, once the high altarpiece of the church of San Martino.

Lost art

An early-16th- century altarpiece depicting The Trinity with

Saints James and Jerome by Girolamo di Santacroce (see right)

has been in the Eremetani Civic Museum since 1894.

The Cat of Saint Andrew

In front of the church is the famous Cat of Saint Andrew

(see photo from 1918 far right) which

traditionally is said to mark the highest point of the city. It's a rough stone

lion taken as a war trophy from the fortress of Este in 1209 by local

residents. When the lion was returned at the end of the conflict a

copy was made.

After being knocked down several times in recent years (the most recent in

2013, when a van hit it) it was finally reassembled by Paduan sculptor

Antonio Pennello. |

|

|

Art

Art Giotto

- it was as a Giotto

that Petrarch bequeathed it to his friend Francesco da Carrara.

Giotto

- it was as a Giotto

that Petrarch bequeathed it to his friend Francesco da Carrara.

History

History

History

History

History

History

. Inside it's aisleless tall and octagonal (or maybe

square with the corners chopped off) and decorated with the marble panels

and stucco typical of the 18th century. Sharp left as you enter, and down

some stairs, is the unserene Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre. The small Presbytery and separate

choir beyond are all marble and stucco too, but the large sacristy is much

plainer and more solemn.

. Inside it's aisleless tall and octagonal (or maybe

square with the corners chopped off) and decorated with the marble panels

and stucco typical of the 18th century. Sharp left as you enter, and down

some stairs, is the unserene Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre. The small Presbytery and separate

choir beyond are all marble and stucco too, but the large sacristy is much

plainer and more solemn.

the aisles and over the

side altars are works from various sources and periods, including Saint

Francis Xavier by Natale Plache, from the Gesuiti church demolished

in the late 18th century and a Saint Martin in Glory of the 17th

century, once the high altarpiece of the church of San Martino.

the aisles and over the

side altars are works from various sources and periods, including Saint

Francis Xavier by Natale Plache, from the Gesuiti church demolished

in the late 18th century and a Saint Martin in Glory of the 17th

century, once the high altarpiece of the church of San Martino.