|

San Giacomo

dell’Orio 1225 |

||

|

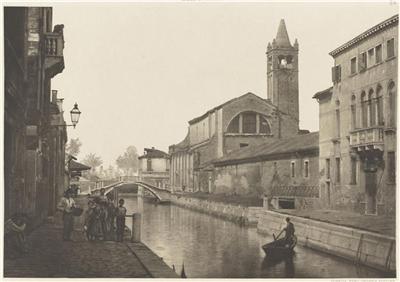

History Tradition says that the church was founded in the 8th century, but the first documented reference dates to 1120. The church is dedicated to Saint James the Greater, the apostle. The dell'Orio part is said by some to be a corruption of del lauro (of the bay tree) and to refer to a tree said to have been growing on the site when the church was founded. Competing theories suggest wolves, a contraction of Apostolo, the rio, a swamp (luprio) or the Orio family. The church was remodelled and enlarged in 1225, using funds provided by the Badoer and Da Mula familes. Further rebuilding following an earthquake in 1345 saw the addition of the transept and ship's keel roof. More rebuilding took place at the beginning of the 16th century, with some further restoration work in 1903-12, when the new sacristy was built. The church The main entrance faces the canal to the north into Campiello del Piovan (see photo right) with its back and apses into Campo San Giacomo (see below right). The statue of Saint James on the segmental pediment over the door dates from the 17th century. The interior A Latin cross plan with granite columns separating the nave from the side aisles each topped with very old, or ancient, capitals. The thick columns appear even chunkier due to the raising of the floor resulting in them losing height over the centuries. On the right-hand side is a surprising second aisle, making for an asymmetrical space. This extra space contains the exposed wall of the old church and two unmatching columns, including the gem-like verde antico column said to have been sacked from Byzantium in 1204 - it's at the centre in the interior photo below right. It was later much admired by John Ruskin and Gabriele d'Annunzio (see below). Also surprising are the two sacristies and the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament, a sudden burst of 17th-century decorative overkill and balustrades and a painted dome. There's also the 14th-century ship's-keel roof to admire. Art highlights Lorenzo Lotto's high altarpiece of the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints James the Elder, Andrew, Cosmas and Damian is dated 1546, shortly before he departed Venice for the Marches, in a huff at potential commissions drying up. There's also a good Paolo Veneziano-attributed painted Crucifix of c.1324 above. The old sacristy off of the left transept was built in 1568 and decorated in 1575. The walls and ceiling are full of works by Palma il Giovane (the great-nephew of Palma il Vecchio) - this church has 12 paintings by him. In here the scenes are of The Passion along with typological equivalents from the Old Testament from 1575-81.  Saint John the Baptist Preaching by Francesco Bassano (father of the more famous Jacopo), in the new sacristy to the right of the apse, dates to c.1570 and contains portraits of the artist's family and of Titian, on the far left wearing a red hat. There's a Virgin in Glory with Saints John and Nicholas of Bari in here too by the same artist, with an arguable amount of involvement by his son. The new sacristy also has a ceiling panel by Paolo Veronese, or his studio, of The Holy Ghost Appearing to the Theological Virtues from 1577, with four roundels, each depicting one of the Doctors of the Church. Formerly in the right transept, the ceiling was moved here with new framing when the new sacristy was built during the rebuilding of 1903-12. He also has a Saints Jerome, Lawrence and Prospero (see right), painted for the Malipiero Chapel here in 1582, which has seen much restoration and is very 'workshop of' too. It originally had a predella illustrating the martyrdoms of the three saints. There are frescoes by Jacopo Guarana in the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament to the right of the apse. But the weirdest painting here, and maybe in the whole of Venice, is the deceptively innocently-named Miracle of the Virgin (aka The Funeral of the Virgin) an episode rarely depicted. It was painted by Gaetano Zompini in the 18th century (see below right) who also painted the dome fresco in the nearby San Nicolò da Tolentino, but was best known for his engravings of hawkers. What it shows is a pagan high priest who has run up and attempted to overturn Mary's bier, only to find himself miraculously thrown to the ground with his hands ripped off and still attached to the coffin. He then appeals to Saint Peter, according to The Golden Legend, and is healed and converted. This painting is ignored by most guidebooks but it features in David Hewson's novel Lucifer's Shadow, as does another bizarre painting in the church of San Cassiano. Also strange (on the left wall as you enter) is the painting of The Miracle of Saint James Resurrecting the Rooster, one of his odder miracles, but the painting is a bit too dingy to easily make out what's going on. It's by Antonio Palma, who was Palma Vecchio's nephew and the father of Palma Giovane. Lost art An oval ceiling painting of The Coronation of the Virgin by Veronese over the altar of the Immaculate Conception, in the left aisle near the entrance, vanished some time before 1771. Campanile 44m (143 ft) manual bells The original was demolished in 1220 because it was unsafe. The current tower dates from the 1225 rebuilding. It was seriously damaged by the earthquake of 1347 and was restored in 1360. Ruskin wrote A most interesting church, of the early thirteenth century, but grievously restored. Its capitals have been already noticed as characteristic of the earliest Gothic; and it is said to contain four works of Paul Veronese, but I have not examined them. The pulpit is admired by the Italians, but is utterly worthless. The verde-antique pillar in the south transept is a very noble example of the "Jewel Shaft." Gabriele d'Annunzio wrote He described tha verde-antique column as 'the fossilized compression of an immense verdant forest'. The church in literature Just before the climactic confrontation in The Mirror Thief by Martin Seay the central character, Crivano, enters an unnamed church 'Looking at everything. The ship's-keel roof. Fossil snails in the floor. A green marble column taken during the Crusades. Paintings of the saints and the Virgin. One shadowy canvas - Saint John the Baptist preaching to a rapt and reverent crowd...' he then ponders the work and life of Francesco Bassano. Opening times Monday to Saturday: 10.30 - 5.00 A Chorus Church Vaporetto San Stae or Riva di Biasio |

Photo of The Miracle of the Virgin by Gaetano Zompini taken by Christopher Martyn |

|

|

Vaporetto Piazzale Roma |

|

|

History Dedicated to San Simeon Profeta (Saint Simon the Apostle) this church is known as San Simeon Grande to distinguish it from the larger church of San Simeon Piccolo nearby. (Although some say that the grande and piccolo refer to the size of their parishes.) This church was said to have been founded in 967, but the first documented mention is from 1073. It was rebuilt in the 12th-13th centuries and then again in the early 18th century by Dominico Margutti, with interior renovation 1750-1755. This latter work was said to have been ordered by the city's sanitation department who were worried about the plague victims buried under the floor following the 1630 epidemic and so ordered the floor to be relaid. Restoration work in the 19th century revealed that the old floor was still intact under the new. On 18th March 1795 a part of the ceiling fell on, and killed, noblewoman Lucrezia Cappello while she prayed. It is not unusual amongst Venetian churches in having a Greek temple façade, this one dating from 1757 and attributed to Giorgio Massari. It was further renovated in 1861, with work in 2015/6 too. Interior Has pleasingly rough-looking original columns, with Byzantine capitals probably dating from the 13th century, an asymmetric layout - the right-hand aisle is much wider than the left - and round arches. Statues of the Twelve Apostles over the columns in the nave are early 17th century and by Francesco Terilli. The chapel to the right of the chancel has some nice (18th century?) frescoing on the ceiling that's considerably corroded lower down.

Art highlights |

||

|

History Tradition says the church, also known as Santi Simeone e Guida (Saints Simon and Jude) was founded in 966, but the first written reference is from 1138 and later to work after a fire in 1149. This original church was demolished in 1718 - three floor levels were found, one on top of the other - and rebuilt by Giovanni Scalfarotto who was inspired by the dome of the Pantheon in Rome, it is said. The rebuilding was helped by money from a lottery authorised by the Council of Ten in 1733, and run by a priest called Manera. Scalfarotto (who had Piranesi as an apprentice for a while) had his name carved into the architrave of the façade. This church was consecrated in 1738, and was one of the last religious buildings erected in Venice. This last rebuilding enlarged the church, it is said, so as to make it bigger than the nearby San Simeon Grande, but the names of both churches have stuck. Although some say that the grande and piccolo refer to the size of the parishes. This was recently the only church in Venice to celebrate the traditional Latin Mass daily. The church The porch is in the form of a Greek temple. One of the four columns was replaced following the destruction of the original by enemy bombs on the night of February 26th/27th 1918. The triangular pediment contains a relief showing The Martyrdom of Saints Simon and Jude, the church's name saints, by Francesco Penso. The statue on the lantern on the dome is of The Redeemer by Michele Fanolli Interior Supposedly inspired by the Salute and built with the intention of being its equivalent at the other end of the Grand Canal. It's circular and unkempt with a domed central space with a big sheet for a ceiling (in 2017) and four altars with ordinary 18th century altarpieces. Pulpits to left and right. The apse is also domed, with semi circular wings with statues in niches and on the altar. There's an impressively realistic Pieta (although a full-sized chap on a woman's lap is never going to be comfortable) in a niche to the left. There had long been sparse and tantalising reports of an unusual octagonal crypt with four corridors of tombs radiating out, decorated with frescoes depicting images of death and the Day of Judgement. These rumours were finally confirmed in January 2017 (see below). Campanile 3m (10ft) above roof of church, manual bells Dating from the Scalfarotto rebuilding and visible from the courtyard behind and to the left of the church. Ruskin wrote One of the ugliest churches in Venice or elsewhere. Its black dome, like an unusual species of gasometer, is the admiration of modern Italian architects. Lorenzetti wrote ...a high ungraceful copper-covered dome, of a shape disproportionate to the size of the building supporting it. Robert Coover (in Pinocchio in Venice) wrote ...misshapen little San Simeon Piccolo with its outsized portico and squeezed dome...the popping green bubble on San Simeon the Dwarf rising through the fog with the erotic suggestion of a Venetian double entendre. Napoleon said I have seen churches without domes before, but I’ve never, until now, seen a dome without a church. The church in art  Canaletto’s The Grand Canal with San Simeon Piccolo from 1742 in London’s National Gallery shows the church with the dirty black dome that Ruskin so hated. It does look better, and less dominating, having been cleaned and gone green. The church had only just been completed when the view was painted - a builders' hut is visible by the steps. An earlier Canaletto view from 1726/7 in the Royal Collection in London shows the steps unfinished. Guardi painted a similar view in 1780 (see above) now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It also shows the church of Santa Lucia to the right, which was demolished to make way for the railway station. There's a watercolour of The Upper End of the Grand Canal by Turner from 1840 featuring the church and one by William Russell Flint called Three Green Domes, in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight. Opening times In 2017 the sacristan here told me that the church is now to open every day except Monday, with access to the unmissable crypt (see below). But... Update January 2024 The church now seems to have closed again and a sign on the door says 'the church’s crypt is permanently closed for security reasons and it cannot be visited'. Vaporetto Ferrovia map |

|

|

|

The Crypt |

||

|

Walking past San

Simeon one morning in January 2017 I noticed that it was open, which is very rare. Getting

inside we found that the famous and mysterious crypt was open too,

which has never been known. I say famous but, although what

I've read has been tantalising, the crypt is not often mentioned in guidebooks

and the like, and if it is the details are sparse. We paid the sacristan

in the church €2 each and were each given a candle. There

is only one light down there, so another source is needed to explore properly,

and I wished I'd brought a torch. It's a warren of tunnels, radiating from

a central octagonal domed space, which has the light. The walls and

ceilings are totally

covered in painted decoration and images, with spooky niches and chambers leading

off. The painting

is rough in execution and macabre in style, with reclining bodies,

Passion scenes and skeletons featured. The burial chambers |

|

|

|

||

|

The church Said to have been founded in 966 and dedicated to Sant'Eustacchio (Saint Eustace, the commander of Trajan's army, who is said to have seen the crucifix between the antlers of a deer whilst hunting) who becomes San Stae in Venetian dialect. The first written references to the church appear in the 11th century. This church, rebuilt in the 12th century following a fire, was side-on to the Grand Canal (see the detail from a map below) and was demolished in 1678. The current church was then built from 1683 by Giovanni Grassi, who realigned it to face the Grand Canal. The façade of 1709 is by Domenico Rossi, whose design was the winner amongst twelve designs submitted in competition. It was paid for by a legacy in the will of Doge Alvise Mocenigo and features the work of seven sculptors, the statues being of various virtues, saints and angels. The two reliefs are The lion lowers its head before St Eustace and The Emperor Hadrian has Eustace and his relatives thrown in a red-hot bronze ox. The church underwent restoration recently by the Swiss Pro-Venezia Committee, and is often used for exhibitions and concerts. Interior A calm, pale and Palladian interior, and very light, due to the Palladio-inspired semi-circular windows, a feature of the Redentore. An aisleless nave with three side chapels easch side. The interior is as statue-populated as the façade with lots more angels. A spooky bone-decorated tomb slab of Doge Alvise Mocenigo (in the middle of the pavement) who had paid for Rossi's façade. The Latin inscription on his tomb reads 'Fame and vanity are here buried together with the body'. The chapel first on the left is dedicated to the Foscarini family and includes the tomb of Antonio Foscarini, reinterred here with honours after being exonerated of the charge of treason for which he had been executed in 1622.

Art highlights

|

|

|

|

History Named in the Venetian dialect for San Giovanni Battista Decollato (the Decapitated Saint John the Baptist) the church was founded in the 8th century, legend has it, but the first documentary evidence dates the founding to 1007, built at the expense of the Venier family. Rebuilding then took place in 1213 (courtesy of the Pesaro family) and in 1703 when the current façade was built. In 1358, on August 29th, the Venetian navy defeated the Genoese fleet off Negroponte. As the date was the feast day of Salome's dance the saint was credited with the victory and the doge vowed to visit this church on the feast day every year, but this only lasted a few years, as the church was too small, and the commemoration transferred to San Marco. The decaying church here was suppressed by Napoleon and closed in 1818 and put to use as a warehouse. In 1945 extensive restoration work was undertaken to return the church to something like its original appearance. This involved the reopening of the circular window on the façade and the demolition of the stuccoed ceiling to reveal the ship's keel roof underneath and the small windows just beneath it. It was during these works that the frescoes in the left apse, Byzantine in style and amongst the oldest in Venice (see one of them below far right) were discovered by Michelangelo Muraro.  Having then been closed for almost 20 years, and after more restoration work (which revealed the fresco of Saint Michael in the right apse (see right) the church re-opened in 1994. (A guidebook I have from 1972 says that the church was then closed but you could ask at the convent next door for a nun to let you in with a very large key). On the wall facing the campo there is a relief of the just-severed head of John the Baptist in a basin being shown to Salomé. The relief was originally attached to a nearby building next to the bridge, but was later moved here. The church is now used for Russian Orthodox services (see interior photo with iconostasis right). Interior The church feels ancient, dark and bare, with a nicely weathered look. The nave has its wooden ships-keel roof and is divided from the similarly-roofed aisles by two colonnades of four columns of Greek marble with 11th-century Byzantine-style Corinthian capitals with later gothic arches above. It has painted walls and the lovely old fresco fragments discovered during the restoration and dating from the 11th to 13th centuries. They were originally taken down and travelled widely before returning. The Saint Helena (see below right) was returned to its place on the right wall of the Crucifix Chapel, left of the presbytery. The large Annunciation fragment was on the triumphal arch of the chapel but is now on the left wall. Both date to c.1290. The four saints heads below Saint Helena are John, Peter, Thomas and Martius. Frescoes, especially ones this old, are rare in Venice as the city's damp atmosphere is not good for them. Local colour  According to a tradition dating from the 16th century the carving of the head of John the Baptist mentioned above (and pictured right) is said to be a representation of Biagio Cargnio, a butcher who was beheaded and quartered as punishment for putting the meat of murdered children into his sausages and stews. His quartered body parts were put on display on the Ponte dei Squartai (the Bridge of the Quartered Men) on the Rio del Tolentini. His house and shop stood in the nearby fondamenta named after him, Riva di Biasio, but both were razed to the ground. The carving could be found smeared with mud well into the last century, this being evidence of Venetians' long and unforgiving memories. On November 21 in 1500 a whole family was murdered by a Franciscan priest who officiated at San Zan Degola. He was executed in the Piazza San Marco on December 19th, having first had his right hand cut off in front of the door of the family he'd robbed and murdered. Campanile 20m (65ft) manual bells  The map of 1635 (detail right) shows a taller detached tower with a tall spire which was demolished in the early 18th century and replaced by the current short tower, squeezed between the church and an adjacent house.

Opening times |

|

|

|

History A wooden convent and church was built 1497-1504, by Franciscan Poor Clare nuns from Sant'Agnese, on recently-reclaimed ground given by the republic. A miracle-working icon lead to the church being named Santa Maria dell'Assunta. Rebuilding, at the behest of Alvise Malipiero, probably by Tullio Lombardo, began in 1503 with the convent habitable by 1505, and the church built between 1523 and 1531. The design of the church was said to have been based on that of its namesake in Rome. Malipiero's patronage continued until his death in 1557 and his burial in the family tomb here. Suppressed in 1805, with the nuns moving to Santa Croce, after which the convent was used as a barracks. The grounds became the Campo di Marte where Austrian officers exercised their horses, and civilians were allowed to ride and walk too. There was a fire in the convent in 1817 and demolition followed in 1900. The church was used as a warehouse for a tobacco factory. The attached prison was built in the 1920s, with prisoners transferred from the prison at San Marco which was still in use until this time. This church is now crumbling away picturesquely as a seemingly forgotten corner of the prison named after it, but it was restored 1961-65. Lost Art All eight altars and their art have long been removed and/or lost. The paintings included a Giovanni Bellini and Titian’s unusually muscular and Michelangelesque John the Baptist (c.1530-33) (see below right), which was commissioned by Girolamo and Pietro Polani, one of them being Titian's landlord at the time, for the family chapel here, dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, to the right of the presbytery here. It was one of three pictures which Pietro Edwards (famed restorer and, in effect, curator of Venice's pictures at the time) pleaded with the French Commissioners not to take from Venice in 1797, along with Titian's Assumption in the Frari and the Bellini in San Giobbe. It was due to be transferred to the Brera in Milan but was given to the Accademia after local protest. A 1485 Virgin and Child with Singing Cherubs by Mantegna went to the Brera in 1808. It was thought to be by Giovanni Bellini (or his school) until 1885 when repainting was removed. The Assumption of the Virgin by Paolo Veronese of c.1580, from the high altar here and benefiting from a cleaning, is now in the Accademia too, in the new Room X dedicated to him. It was given by Simone Lando, a ducal secretary in the Venetian chancery, who also donated in 1584 “to adorn the great chapel” the late, spooky and simple night-time Agony in the Garden of 1582/3 also by Veronese, now in the Brera Milan, which for a time hung against one of the columns here. Ridolfi also mentions 'paintings of the Adulteress, the Centurion and of the sons of Zebedee brought by their mother to Christ' by Veronese hanging here. The latter is probably the Christ meeting the Widow and Sons of Zebedee now in the Musée de Grenoble, they certainly think so, and that it dates to 1565. Also in the Accademia is the recently (2008) restored 16th-century Virgin and Child with Saints John the Baptist and Mark(?) and members of the Marcello Family (see further right), probably by Giambattista del Moro. The Victory of the Inhabitants of Chartres (Carnutesi) over the Normans by Padovanino, is in the Brera in Milan. The subject is unusual and tells of a victory brought about by the display of the Virgin's veil (a pinkish robe in the painting), which came to Chartres cathedral after Charlemagne left it to his son Charles the Bald, who gave it to the cathedral. Campanile 33m (107ft) no bells Late Gothic and similar to that of San Barnaba, with its sugar-loaf spire and pinnacles. Vaporetto Piazzale Roma map

|

|

|

|

Interior |

|

|

|

History Called della Zirada from the Venetian word for 'bend', as the church stands at the bend formed by two canals. Another theory has it that it's named for being the turning point for regattas. Traditionally said to have been founded in 1329 as the oratory of a hospice for poor women, founded by four Venetian noblewomen, Elisabetta Soranzo, Marianna Malipiero, Elisabetta Gradenigo and Francesca Cornaro. The convent and church were rebuilt in 1475 and restored in the 17th century, acquiring a lavish Baroque interior with stucco decoration. Suppressed by Napoleon in 1810 with the convent buildings demolished. The church was said to have been worth visiting before the building of the railway bridge for the views across the lagoon to the alps afforded by its then-grass-covered campo. The church later became the studio of the sculptor Gianni Aricò. The church The Venetian Gothic façade is all that survives from the 1475 rebuilding. It has a portal of Istrian stone with two 14th century bas-reliefs (see right): a Dead Christ and The Calling of Peter and Andrew, the latter with details that excite Venetian boat buffs. Interior There's a barco (nun's gallery) over the door from the 15th century, supported by columns left over from the 14th century church. The rich decoration on the barco was added in the 17th century. The baroque altar of 1679 is by Juste Le Court. Four side altars with 18th century marble statues. Jan Morris says that there is a plaque in honour of the Guild of Refuse Collectors which was mounted above the church door here (presumably inside) during the days of the republic.

Art/Lost art

|

|

|

|

Santissimo Nome di Gesù |

||

|

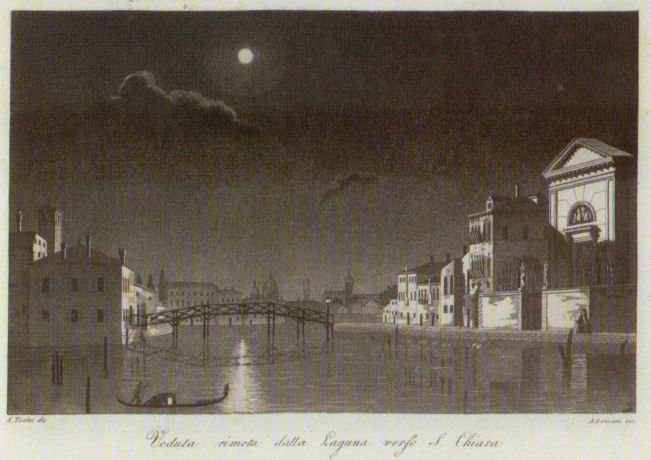

History A small neoclassical church begun by Giovanni Antonio Selva, the architect also responsible for La Fenice and the (equally neo-classical) church of San Maurizio. Don Giuliano Catullo had acquired land here by 1806, but following funding from Count Costanzo Taverna and others work began in 1815, when the demolition of old church complexes was much more common than the building of new ones. The church was completed to the architect's plans in 1834, after his death in 1819, by Antonia Diedo again as with San Maurizio. It is often said that stone and features from San Geminiano were transferred here when it was demolished, but it is also said that Don Catullo disapproved of such recycling. An adjoining convent was built in 1846, for a group of nuns, formed in 1806, led by Sister Maria Vincenza. Three years later the nuns, facing Austrian artillery bombardment fled to San Cassiano and then San Francesco dell Vigna. The complex is now much reduced, tucked into the corner between the Autorimessa multi-storey car park and the Ponte della Libertà, the flyover to Piazzale Roma. The church is currently being used for services by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Interior Very small and neo-classically clean. Tall and tapered ionic columns between the unusual barrel-vaulted apse with decorated domes, with a painted frieze by Borsato and sculptural niches, all lit by lunette clerestory windows. The tabernacle over the high altar is also by Diedo. The flat-roofed nave has a deeply coffered ceiling, with two side altars featuring a pair of paintings by Lattanzi Querena, Saint Francis and The Sacred Heart. The fresco decoration of the vaults of the presbytery were painted by Giuseppe Borsato, as was the Trinity lunette behind the high altar. Campanile Roman-style, on the house next door, taken from San Basso when that church was deconsecrated. The church in art A print called Verduta Rimota della Laguna verso Santa Chiara by Andrea Tosini (1829) (see below) shows this church in the sentimental moonlight. Ruskin wrote Of no importance. Opening times None displayed, but you usually mostly find it open. Vaporetto Piazzale Roma map  |

A photo taken in 1933, the year the car park was built. |

|

|

|