|

History

The Basilica symbolises so much - it's Byzantine to show Venice's

links with the East, it houses the remains of Saint Mark, but is very much

the shrine of the republic, having been built as the Doge's private chapel. It

wasn't built as a cathedral and its dean and clergy were all appointed by

the Signoria and so chosen by the government - so typical of Venice anti-papal

tradition.

The first church built here was dedicated to Saint Theodore, Venice's first

patron saint, who came appropriately from Constantinople. In 829, at the instructions of Doge Justinian Partecipacius,

a chapel enlarging the church was built to also house the remains of Saint Mark the Evangelist

- see

Acquiring Saint Mark's relics

below.

Consecrated in 832, nothing remains of this church, which was damaged in the

fires that raged during the revolt against Doge Pietro IV Candiano in 976

and rebuilt by Doge Pietro Orseolo. We know nothing for certain of the appearance of these

churches, despite much conjecture and some archaeological research. The second church stood for

80 years

before it too was replaced, by the current building, probably begun in 1063

by Doge Domenico Contarini and

consecrated in 1094 by Doge Vitale Falier. Much decorated in later

centuries, the current

structure is substantially this 11th century church, although it was much simpler and

more severe in appearance initially. Its shape and design is said to have

been based on the long-lost church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople

and to have been the work of Greek architects.

It was originally faced with

brick, with most of the marble cladding, friezes and statues that we see

today, including the four famous horses, nearly all plunder from the

4th Crusade's capture and pillage of Constantinople in 1204, added during the first half of the 13th

century. These embellishments give it some of the ancient-art credibility

lacking in a city with no roman past. It functioned initially as a martyrium for

Saint Mark and a palace chapel for the doges, central to

ceremonial Venice. Only later did it take over from

San Pietro di Castello

as the cathedral of Venice, a move enforced by Napoleon in 1807,

thereby putting an end to its ducal-ceremonial function.

The church

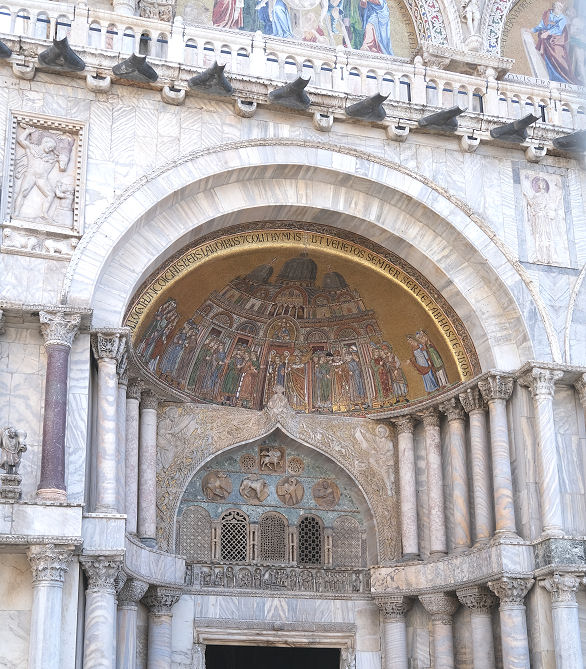

The cycle of mosaics on the famous façade facing Piazza San

Marco read from right to left, as the main approach until relatively

recently was always from the lagoon and the façade facing south was then

the first sight of the church, and therefore had greater importance and impact. The upper level pinnacles and mosaics date from the

15th and 17th centuries respectively. The façade still has a pretty

triumphal aspect despite this later building, including the Gothic upper

arches, detracting from the Byzantine charm somewhat. Of the five mosaics in the

arches only the one over the first door on the left is an original from

the 13th century (see right), the rest being replacements made from the 17th to the

19th centuries. Being the last in the sequence this left-hand mosaic is of

the body of Saint Mark being taken into the Basilica, and shows the façade

as it looked in around 1250. The north façade, onto the Piazzetta dei Leoncini, is a mess of

bits, impressive in parts but not exactly harmoniously combined, although

looking pretty handsome after a recent clean.

importance and impact. The upper level pinnacles and mosaics date from the

15th and 17th centuries respectively. The façade still has a pretty

triumphal aspect despite this later building, including the Gothic upper

arches, detracting from the Byzantine charm somewhat. Of the five mosaics in the

arches only the one over the first door on the left is an original from

the 13th century (see right), the rest being replacements made from the 17th to the

19th centuries. Being the last in the sequence this left-hand mosaic is of

the body of Saint Mark being taken into the Basilica, and shows the façade

as it looked in around 1250. The north façade, onto the Piazzetta dei Leoncini, is a mess of

bits, impressive in parts but not exactly harmoniously combined, although

looking pretty handsome after a recent clean.

Interior

The narthex you cross as soon as you enter stretches across the

width of the façade and a right-angled branch to the left goes up to the

transept. The mosaics in the cupolas of the branch include three depicting

the life of Joseph, an Old Testament figure said to prefigure Saint

Mark. The church is Greek cross shaped with a central dome and a dome

in each of the four square bays, these aisled bays meeting in a crossing dominated by huge piers pierced with passages.

It was just as

overwhelming on first entering as it was on my last visit, 15 years ago,

but the plan is less confusing than I remember.

Everything glows, every

surface is richly decorated with marble of mosaic and almost every vista has a Piranesi-like queasy

complexity. Inside

your progress is roped-off and guided, with nowhere to sit. The no photo

rule applies but is patchily enforced. The interior is

unquestionably Byzantine- influenced - the now-lost Church of the Twelve

Apostles in Constantinople, built by the Emperor Justinian in the 6th

century is often cited as a model - but the altar

being in the presbytery and the presbytery being raised to accommodate the

crypt help make the interior much more Italian. You pay

€2 to

get into this

presbytery and see the Pala d'Oro (behind the altarpiece)

sparklingly lit but behind glass. Saint Mark's sarcophagus is under the

altar.

You pay €3 for

the Treasury, which consists of two rooms. On the left after

paying is a small sanctuary full of reliquaries and saint's bits. Much better

is the room opposite, the actual Treasury in an impressive square and

domed space with some lovely icons and glassware. I found the treasury

inessential but the museum (€5) up a steep staircase to the right of the

entrance to the basilica, is a real treat. Mosaic fragments, up-close views of

mosaics in the left transept, the horses, models and plans, and the view

from the outside terrace, make this a bargain ticket. And there's

the new Sala dei Banchetti, housing mostly tapestries, but also

Paolo Veneziano's cover for the Pala d'Oro mentioned below, and cases of graduals.

The campanile

The first bell tower was built in the 9th century and has been enlarged,

restored and repaired many times since.

The mosaics

It seems likely that the second St Marks, built after the fire of 976,

would have been decorated with mosaics. The mosaic work in the apse of

Santa Maria Assunta on Torcello dates to around the same time as the

current basilica was built.

The earliest mosaics here are the four

saints in niches either side of the door. They are probably late-11th-century - the standing figures in the main apse and the prophets of the

earlier work in the presbytery dome date to the early-12th. On the domes

and vaults in the narthex are scenes from the Old Testament. Inside are

saints and New Testament scenes like the Pentecost and the

Ascension.

The degree to

which the devastating fire which swept Venice in 1106 destroyed earlier

mosaics and/or necessitated their replacements is much argued. Work

continued here into the late 12th century, undoubtedly the most important

century for the interior mosaics, as did the work in the apse and

on the huge Last Judgement on Torcello. It is thought that craftsmen

brought from Byzantium were responsible, at least initially, before locals

learnt from them and continued. Possibly. Later centuries saw the need

for, and the carrying out of, considerable repairs. Paolo Uccello and

Andrea del Castagno were amongst the artists called in to repair and train.

Later interventions were more likely to replace old and 'ugly' mosaics

with new works. The worst offenders here were Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, Salviati

and Palma Giovane. The new Apocalypse mosaic at the west end of the

nave was one of these additions. Only in 1610 was a decree issued stopping this

practice, as the old works had often been said to have been better than

the new. This decree had to be repeated several times so may not have been

very effective. As the skill and number of mosaicists declined, the rock

bottom was reached in the 19th century, with repairs and materials of

particularly poor quality.

Some 110 scenes in the mosaics in the atrium are said to be derived from miniatures

in the Cotton Genesis, a 6th-century Greek manuscript (now in the British Library) taken

from Constantinople. Or Alexandria - expert opinions differ.

The Pala d'Oro

Much added to, the Pal d'Oro

(see photo right) is made of gold and silver and now has 187

enamel plaques and almost 2000 gems. It was originally an antependium

(altar frontal) made for Doge Pietro Orseolo in 976, remade and placed at

the back of the altar in 1105. Then remade again in 1209 and 1345. The original

bottom section shows scenes from the Life of St Mark - these were

originally along the very bottom but now go along the top and down the

sides of the central section. The main central section has Christ in the

centre, with the Four Evangelists in circular panels and flanking rows of

the Apostles, with angels above and the twelve prophets below.

The 1209 'renewal' saw the addition along the top of

the seven larger panels looted from Constantinople. Here six panels of

scenes from the Gospels flank the Archangel Michael. These enamel panels

probably came from the church of the monastery of the Pantocrator in Constantinople. Some form

of Byzantine imperial involvement is suggested by one of the early 12th

Century enamel panels depicting Empress Irene - a balancing panel of her

husband Emperor Alexios I was removed at a later date. She is now balanced

by a panel of Angelo Falier, procurator during the enlargement of 1209. The 1345 work saw the goldsmith Giovanni Paolo

Benesegna commissioned to make a gothic frame and add more precious

stones.

In 1432/4 Paolo Veneziano was commissioned to paint a wooden cover

for the Pala d'Oro which was only displayed on the feast days of the

Nativity and Easter, being hoisted up on those days by a system of pulleys. This cover (see

photo right) which became known as the Pala Feriale, or

“weekday altarpiece”, was painted by Paolo with the help of his sons Luca

and Giovanni - all three signed the work, dated 1345. The original framing

elements are lost so Paolo's panels are presented now in two rows.

On the top row The Man of Sorrows is flanked on the left by the

Virgin, Saints Theodore and Mark, and on the right by Saints John the Evangelist, Peter, and

Nicholas of Myra. Scenes of the life of Saint Mark and the theft of

his relics are in the row below. In the 15th century this cover

was replaced with

a plain wooden panel and the Venezianos' panels are now displayed in the

San Marco Museum.

The 4th Crusade spoils

The 4th crusade set out in 1402 to wrest control of Holy Christian sites

back from the infidel, but more famously resulted in the invasion and

sacking of Christian Constantinople in what began with a request to sort

out a succession crisis and ended up in murder and pillage. It was to

prove the beginning of the end for the great empire, but was arguably

retaliation for the pogrom-like Massacre of the Latins which had seen the

slaughter of Catholics, men. women and children, mostly from Venice, Genoa

and Pisa, during the reign of Emperor Alexios II Komenenos decades

previously. 4,000 of those who survived had then been sold as slaves to

the Seljuk Turks.

The four gilded bronze horses, probably

spoils taken to Constantinople in the 4th-6th century, were removed from the Hippodrome

there,

presumably, or nearby, and set up over the main entrance here in the 1254.

Venice having no Roman past itself, the horses would've been seen as a

suitably symbolic indicator of Venice's ambition to be the new Rome. They

are actually made of copper, with a little (c.2%) tin, so are not strictly

bronze. The date of their creation has been previously said to be anything

from 400BC to 400AD, but is now narrowed to after the 2nd century AD, due

to the difficulty of casting copper and the use of mercury gilding making

an earlier date unlikely. Napoleon

took them to Paris in 1797, where they ended up on top of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in the Tuilleries, until they were returned to Venice in 1815

following the defeat of Napoleon. They

were moved indoors

to protect them from acid rain and replaced by copies in the

1970s.

The Tetrarchs - a porphyry sculpture of

the then four rulers of the Roman Empire, of around 300 (see right)

possibly taken from the Philadelphion in Constantinople. They are probably

the bearded emperors Diocletion and Maximilian and the clean-shaven

Caesars Galerius and Constantius I. In Francesco Sansovino's

Guidebook to Venice of 1561 he tells a story of four merchants who

smuggled treasures into Venice, but deciding that the proceeds would have

to be split too many ways a pair decided to poison the other two, with the

other two having the same idea, so all four were poisoned. He reports that

'in the opinion of the mob' these four are the figures depicted in

the Tetrarchs sculpture, but admits that it is just a fable. The

missing heel and plinth fragment was found in Istanbul in the 1960s and is

now in the Archeology Museum there.

Marble revetments, floors, columns (and their bases

and capitals) and panels of sculpture, stripped from the churches of

Constantinople. Mostly their origins are untraceable, but capitals and

columns from the 6th-century church of Saint Polyeuktos are distinctive, like

the misnamed pilastro acritani.

Acquiring Saint Mark's relics

Saint Mark had been the Bishop of nearby

Aquileia, where he had been sent by Saint Peter. On his way,

in his boat, passing near where Venice was to be built, he had a vision

telling him that his body would find its final resting place nearby. He

was martyred in Alexandria, his next posting, in 68AD.

Around 828 some Venetian merchants travelled to Alexandria intending

to 'acquire' the relics of Saint Mark. Two of their number, Buono da

Malamocco and Rustico da Torcello. learnt from the custodians of the

sanctuary where the saints bones were kept that they were in danger of

being destroyed by the Arab governor of Alexandria who was going to

use marble and columns from Christian churches to build himself a palace

in the city of Babylon. Or so the story goes. The custodians having been talked around, the

saint's remains were replaced by the nearby body of Saint Claudia and the relics

loaded aboard ship, hidden in wicker baskets and covered with cabbage

leaves and pork, the latter considered unclean by Muslims. So when customs

men came to inspect the cargo their disgust made them wave the baskets

through without inspection.

On the voyage back to Venice the saint appeared to the dozing sailors and saved

them from shipwreck. The relics were initially

placed in a corner of the Ducal Palace awaiting the building of the new

basilica. Saint Mark thereby became the patron saint of

Venice, replacing Saint Theodore. In 976 the relics were lost in a fire. Only at a reconsecration in 1094

did the the

saint himself reveal the location of his remains to Doge Vitale Falier and the

people gathered in the basilica, by extending an arm from a pier on the right hand side

of the nave. The church was

also filled

with a sweet smell.

Other relics

The relics housed here have included an arm of Saint George, a

stool which belonged to the Virgin, a finger of Mary Magdalene, a knife

used at the last supper, the stone on which John the Baptist was beheaded,

a rib of Saint Stephen, and the sword Saint Peter used to cut off

Malchus's right ear. The latter, a servant of Caiaphas, being one of those

attempting to arrest Jesus.

Lost art

There is a 12th century mosaic fragment of a male head, a

personification of Mesopotamia, removed from the west dome here, in the

Victoria & Albert Museum in London. It was removed by the restorers

Salviati in 1867.

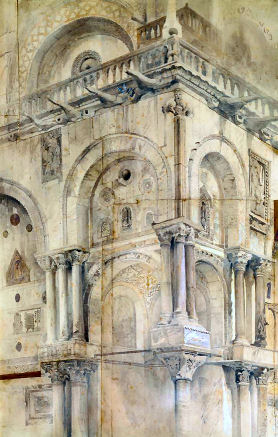

The Basilica in art

There are countless views of the Piazza which feature the

Basilica. Gentile Bellini's

Procession of the True Cross in Piazza San Marco of 1496 (see

right) was

painted for the Grand Hall of the

Scuola Grande di San Giovanni

Evangelista but is now in the Accademia. It shows us how the

Basilica looked in the late 15th century, with its original lunette

mosaics. Three paintings by Canaletto of the interior during Easter

celebrations exist - two in the British Royal Collection and one in

Montreal. John Ruskin made many fine sketches of details (see right).

There are lots by Sickert.

Dickens wrote (in

Pictures from Italy)

A grand and dreamy structure,

of immense proportions; golden with old mosaics; redolent of perfumes; dim

with the smoke of incense; costly in treasure of precious stones and

metals, glittering through iron bars; holy with the bodies of deceased

saints; rainbow-hued with windows of stained glass; dark with carved woods

and coloured marbles; obscure in its vast heights, and lengthened

distances; shining with silver lamps and winking lights; unreal,

fantastic, solemn, inconceivable throughout.

Opening times

October – March/April (Easter):

Basilica: 9.30 - 5.00 (last admission 4.45)

Sunday and holidays:

2.00 - 4.00 (entrance free)

St. Mark’s Museum: 9.45– 4.45 €5

Pala d’Oro: 9.45 - 4.00 Sunday and holidays: 2.00 - 4.00 €2

Treasury: 9.45 - 4.00 Sunday and holidays: 2.00 - 4.00 €3

March/April (Easter) – November:

Basilica: 9.45 - 5.00 (last admission 4.45) Sunday and holidays: 2.00 -

5.00 (entrance free)

St. Mark’s Museum: 9.45 - 4.45 €5

Pala d’Oro: 9.45 - 5.00 Sunday and holidays: 2.00 - 5.00 €2

Treasury: 9.45- 5.00 Sunday and holidays: 2.00 - 5.00 €3

website

Vaporetto Vallaresso (San Marco)

map

|

|

San Teodoro

Only in 2024 have I

found out about this church.

The small church of San Teodoro is to be found now within the San Marco

Basilica complex. A church dedicated to Venice's earliest patron saint

seems to have existed by the 8th century in the current Piazzetta dei

Leoncini. It was a simple with an aisle and two naves, a front narthex and

a semicircular apse. An earlier and smaller church dedicated to Saint Mark

sat between this church of San Teodoro from the first Palazzo Ducale. This

first church of San Teodoro was demolished in the 12th century during the

construction of the current basilica of San Marco

A new church was built beyond the apse-end of the Basilica. This was a in

a Renaissance-style and designed by Giorgio Spavento. Work began in 1486

under the guidance of Maestro Domenico and was completed within only a few

years. The façade originally had frescoes by Tommaso di Giorgio, but these

are long lost. Part of the building is now within the structure of the

Palazzo Ducale overlooking the Rio di Palazzo. The building has been used

as a seat of the Inquisition and later as a sacristy. Restoration work

took place in 1961.

The façade is bare brick. Over the entrance portal is a lunette painting

from 1490 by Sebastiano da Lugano and Matteo da Valle. The only art

reported inside is a Nativity, an early work by Giambattista

Tiepolo.

|